Umami

The delicious taste sensation

I regularly take part in a pub quiz, and one of the questions that recently came up was: name the five basic tastes. Six of us in the team; we could only name four. Sweet, sour, salty and bitter. We argued as to whether savoury was a valid taste but couldn’t be sure. I’ve already told you what number five is, in the title, but we wouldn’t have guessed it in a hundred years. I suppose if I’d watched more cookery programs in the last twenty years, or was a connoisseur of Japanese food, I might have known. When the answer was finally revealed, all the cooks were like “Dur, everyone knows that”, while in my somewhat ancient age group, only the Retired Teachers were smug enough to know the answer.

So what happened?

The Tongue Map

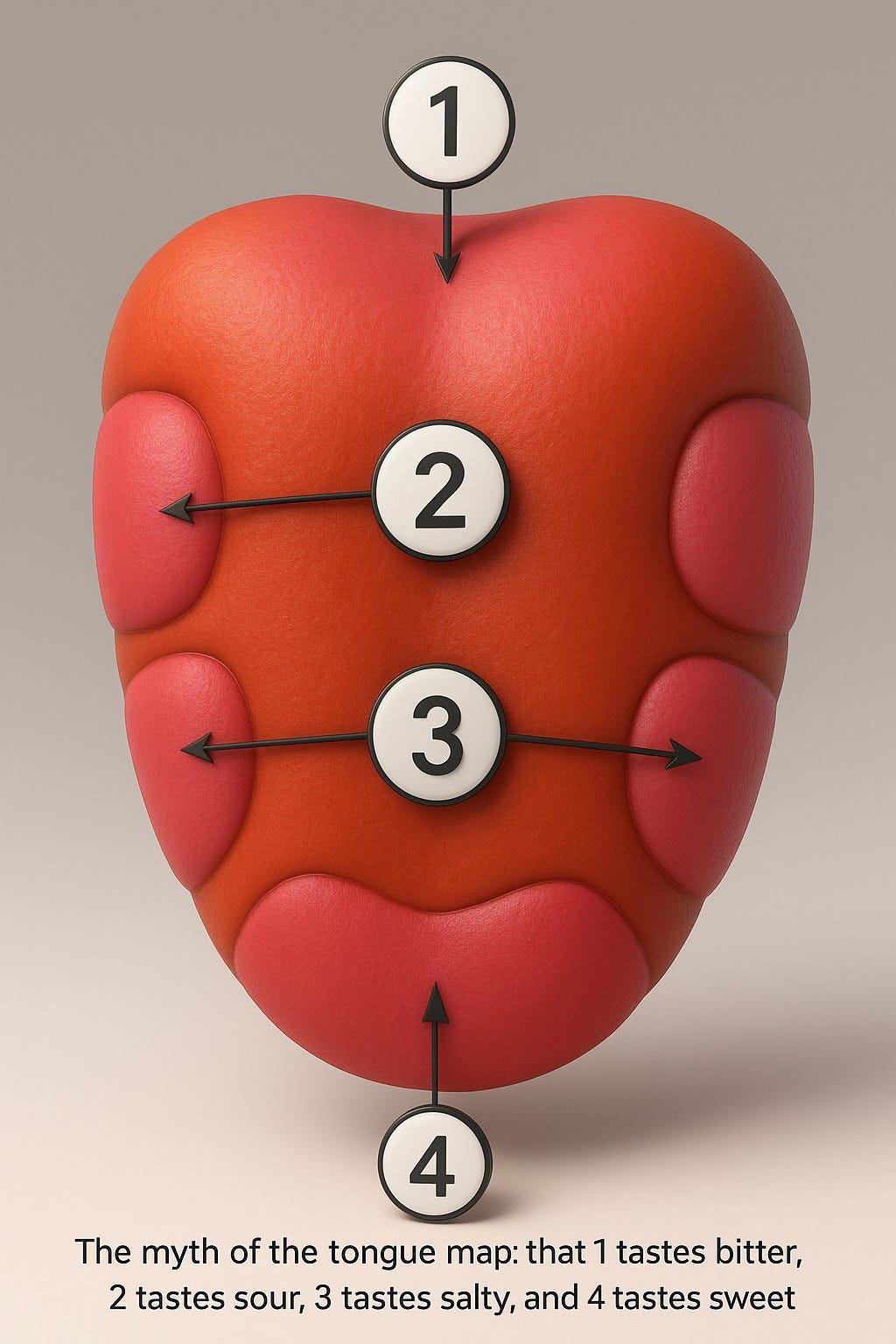

I was schooled in the 1960s and 70s, and taught erroneously it seems, that there are four tastes and they are each associated with a different part of the tongue.

This map above was created by a Harvard psychologist called Edwin Boring in 1942, and went on to be widely adopted in textbooks and educational materials, being drummed into every child’s brain. Boring didn’t discover the tongue map, rather he took work that had been published by a German scientist (David P. Hänig) some 40 years earlier, in a paper titled “Zur Psychophysik des Geschmackssinnes” (The Psychophysics of Taste).

Herr Hänig’s original findings showed that while all areas of the tongue are sensitive to tastes, certain areas were more sensitive to certain flavors. Boring reinterpreted and simplified Hänig’s graphs in his book Sensation and Perception in the History of Experimental Psychology, exaggerating the minor differences in sensitivity, and drawing the conclusion that certain areas of the tongue could only detect specific tastes.

It wasn’t until 1974 when Hänig’s paper was re-examined by Virginia Collings that the errors made by Boring received full publicity.

Delicious

While Herr Hänig was busy with his paper, a Japanese chemist (Kikunae Ikeda) working around the same time scientifically identified a new distinct taste attributed to glutamic acid, which he named “umami”. The word more or less means “delicious”, but for most of its life was confined to Japan. After its discovery it took eighty years before it was proved that there are specific receptors in the tongue and stomach able to detect the glutamate taste, and in 1985 umami was officially recognised internationally as taste number five.

The Western public weren’t having it though, preferring to adopt the term “savoury” instead. Scientifically speaking, savoury is too broad a term to be a taste, and you’ll note it doesn’t appear on the tongue map. Besides, in the 1980s, loanwords from Japan weren’t a thing and you’d get called names for trying to use one. By the early 2000s, thanks to the proliferation of professional chefs, dieticians, and media articles about cooking, umami began to creep into the public lexicon, and by the 2010s it finally cemented its place as the go-to answer for taste number five in pub quizzes across the land.

How do you define delicious? The four basic tastes all work on their own, and can be easily recognised as such. Umami requires an aroma to be activated, and is often an enhancer of other flavours rather than a flavour in its own right. Think monosodium glutamate (MSG). Good old British cooking likely has no umami, whereas French and Italian cooking are full of it, even though they didn’t know it until recently. Curry? Definitely umami. Far Eastern cookery? Umami throughout.

Food is such a big part of the human experience, I’m sure you’ll love to leave your own umami experiences in the comments.